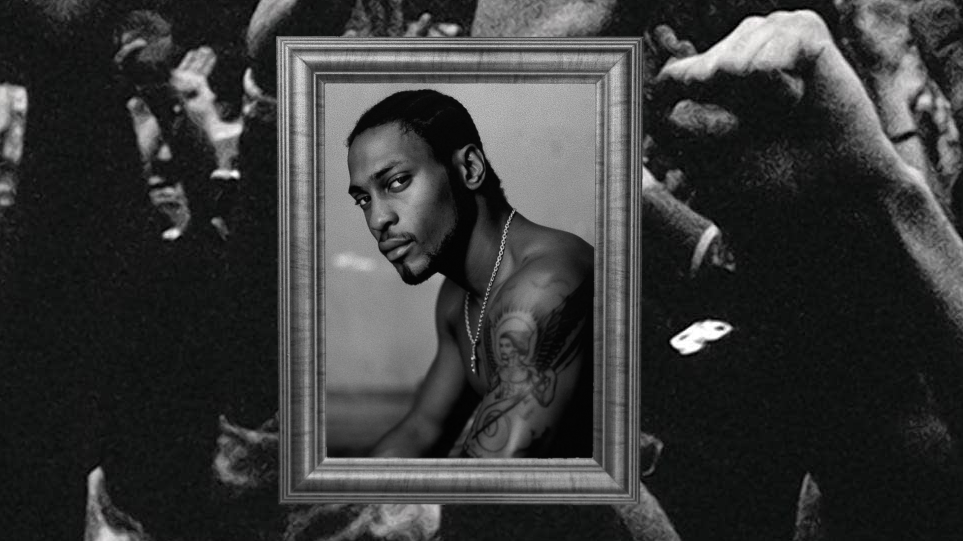

Black Messiah — A Love Letter to D’Angelo

Read Time: 8 mins

Music comes and goes. There’s good music, there’s mediocre, and there’s bad. But if you live long enough, every so often something comes along that’s truly life-changing — music that shakes the foundations of who you thought you were; that drags you, kicking and screaming, downriver like an underwater current to somewhere you never imagined you’d end up.

Now, I write a lot about rave culture, acid house and other related bits on this blog, but in 1995, when D’Angelo released Brown Sugar, I was fourteen — full of teenage anger and pubescent malaise. My dad was in the army and, having just been kicked out of school, I was back living with my family in Gütersloh, Germany. My life there revolved mostly around MTV, and my taste in music was still coloured by the last three years in the Midlands: Ned’s Atomic Dustbin, PWEI, Faith No More, The Cure — mixed with the obvious classics: Hendrix, The Who, The Sex Pistols.

My mum, a scouse soul girl, was always banging out rare groove and early-’80s synth-soul classics — The Whispers, Alexander O’Neal, that kind of thing — but up to that point, R&B in its modern form hadn’t really appealed. Then, one night, watching MTV after a particularly nonsensical episode of Beavis and Butt-Head, the video for D’Angelo’s Brown Sugar came on.

Brown Sugar (1995)

In the opening scene, D’Angelo appears with an elderly man in a flat cap, riding an old New York–style lift. The man has that old-school jazz-cat vibe, like a character from a Spike Jonze joint, regaling the young lads with stories of conquests past:

“I’m not talking about that brown sugar you bought at the supermarket, brother. I’m talking about the real brown sugar.”

D’Angelo, all smiles, laughs and says, “A’ight, Pop,” before stepping out of the lift.

“Okay, see ya,” the old man replies in his out-of-time jazz slang, then adds:

“Hey, you goin’ to the same place I am? That’s alright then. Cool.”

A passing of the baton, perhaps. A time-bending moment. Is the old jazzer just another D’Angelo from another time? I don’t know, but I’m fourteen, and I’m locked in.

Brown Sugar begins — a smoky room, jazz clichés abound: red velvet curtains, you know the sort of thing. D’Angelo, slumped over a Wurlitzer piano, starts to play the opening hook. I can only describe what happened next as something approaching a teenage crush — I was smitten. His over-cool, cartoon-cat drawl:

“Brown Sugar, babe, I gets high off your love, don’t know how to behave.”

The sound of that piano, all tremolo, was transporting me. It dripped with soul, echoing a thousand heartbreaks in a thousand bourbon-stained dive bars, the acrid air thick with weed and perspiration.

Brown Sugar hit me like a factory reset — a massive U-turn from everything I’d ever heard before. Hearing D’Angelo for the first time was like taking a sandblaster to every preconceived notion I’d had about R&B and music in general. Listening to him alongside Hendrix opened a cosmic portal in my mind — a doorway into psychedelic soul, P-Funk and jazz that had been hidden from me until that moment.

A few months later, when D’Angelo played Later… with Jools Holland, it blew my tiny mind. That performance quickly spiralled into an obsession — not just with his music, but with the instruments themselves. Things began to fall into place. I felt the funk and wanted more. I changed the style and pace I drummed at and began discovering music I’d probably never have considered before. I found Portishead simply by trying to learn more about the Rhodes and Wurlitzer pianos that featured so heavily on Brown Sugar, which in turn led me to Lalo Schifrin and a host of others.

Most of Brown Sugar was produced with a kind of hip hop–meets–jazz aesthetic — live keys and guitars over 12-bit breakbeats — a sound that opened up a whole world of releases on labels like Acid Jazz and Talkin’ Loud, as well as the jazzier side of hip hop (Souls of Mischief, Pharcyde, A Tribe Called Quest, and of course Jazzmatazz). This wasn’t the first time I’d heard soul music; as I mentioned, I’d grown up listening to Marvin, Isaac and the later synth-soul contingent, and I was already into Prince in a big way. But there was something different about D’Angelo — a kind of lazy street soul, suave yet authentic. There was no big act, no costumes, no themes — just a lad in street clothes being the coolest, most talented motherfucker on the planet as if that was nothing.

Voodoo (2000)

Things went quiet for a bit. My record and CD collections grew in all directions — buckets of R&B, hip hop and jazz. By sixteen, I was hearing D’Angelo in everything that had a groove, from Sabres of Paradise to Coldcut. Obviously, now I’m a forty-four-year-old tubby father of two, I know most of that music shared samples or references. But back then, in the time before the internet, sitting in a damp bedroom in Ceredigion reading sleeve notes, it wasn’t so easy. By eighteen, I was mixing records on shitty Soundlab belt-drive turntables and had a tidy little collection of hip hop, house and early breakbeat. My taste had turned; I wanted something sleazy, funky and dark — and once again, like the Milk Tray man, D’Angelo appeared as if from nowhere, answering my prayers with 2000’s Voodoo.

Voodoo was the album of 2000 for me — gritty, sexy, jagged and dark. Opening with a short voodoo ritual that fades quickly into Playa Playa, with its staccato drums and bass stabs — all rigid and skeletal — Questlove playing his best J Dilla–style off-grid rhythms and D’Angelo’s vocals looming like heavy smoke. Devil’s Pie was mind-blowing, produced by DJ Premier; its rolling bassline lifted from Teddy Pendergrass and pitched down to a demonic growl. Voodoo had something for everyone. Send It On, a reworking of Kool and the Gang’s Sea of Tranquillity, had the diggers in a tizzy; The Root was funky and filthy; and the voyeuristic video for Untitled (How Does It Feel) left me with an awful lot of questions about my own sexuality– Naughty, naughty. Did I want him, or want to be him? Sadly, I never had the body of a Greek god, nor did D’Angelo return my emails. Moving on…

This tidal wave of unwanted sex appeal left D’Angelo self-conscious and uncomfortable with his fame — or, better put, what he felt he was now famous for. Worried he’d become just “that naked guy in the video”, he pretty much disappeared, and after a while turned to drink and drugs. By 2005, most people in his circle had left him behind, and things went dark for a while.

Black Messiah (2014)

Then suddenly, in 2014, as I found myself in a shit personal situation, like the aforementioned Milk Tray man, D’Angelo appeared again — this time with what I genuinely believe to be his greatest album, his What’s Going On — Black Messiah.

Black Messiah was darker, rockier and wiser than anything D’Angelo had released before. He dialled back the smooth, sexy jazz and replaced it with raw analogue guitar soul in the vein of early Sly and the Family Stone. It was unmistakably D’Angelo, but stained with the anger and frustration of its time; remember, this was the year Eric Garner was brutally murdered by NYPD officers. Black Messiah took all that anger and transmuted it into art. Track two, 1000 Deaths (my personal favourite), had me checking my stylus more than once — its distorted funk feels as though all its parts have been squeezed unceremoniously through a Big Muff (the guitar pedal — get your mind out of the gutter).

Though considerably darker than previous releases, such a shining light was D’Angelo that he couldn’t stay in one mood for long. A man whose soul was rooted in love could never not make something like Really Love — its plodding, warm bass and acoustic guitar and string cuts teasing your ears as D’Angelo croons:

“When you call my name, when you love me gently, when you’re walking near me, I’m in really love wit’ you.”

Black Messiah had an edge — a layer of grime that made it a perfect swansong for a man who’d flown too close to the sun, but it had hope built in too. Like Marvin, like Prince, D’Angelo shone a light on the world as it truly is — all its weird anger, sex, love, sadness and passion. I wish it could go on forever.

Tragically, on 14 October 2025, cancer took D’Angelo away from us. But I’ll forever be thankful for everything he made, and every road his music took me down.

RIP D’Angelo x

For more musings, music and middle-aged leftist rants, subscribe to our monthly updates.